Contributor Joshua Brockway

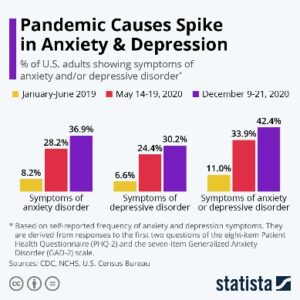

[i] The COVID-19 pandemic has given us a lot to talk about. Most of it amounted to little more than amateur prognostication or low-risk forecasting – the future of work will have more remote employment…oh, you don’t say? Some of it was outright catastrophizing – make sure you stock up on your emergency seeds!! Amidst all the things that we could talk about (while we had nothing else to do), was the topic of mental health. Specifically, all the stress, confusion, disorder, restriction, and uncertainty that we lived with created a surge in documented cases of depression and anxiety. During the pandemic, about 40% of adults in the U.S. reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder, up from about 10% in 2019[ii]. 40%!! That might not mean much out of context, so consider this: if 40% of the chocolate chips in your cookie didn’t taste sweet, you’d sure want to find out what you could do about it.

The COVID-19 pandemic has given us a lot to talk about. Most of it amounted to little more than amateur prognostication or low-risk forecasting – the future of work will have more remote employment…oh, you don’t say? Some of it was outright catastrophizing – make sure you stock up on your emergency seeds!! Amidst all the things that we could talk about (while we had nothing else to do), was the topic of mental health. Specifically, all the stress, confusion, disorder, restriction, and uncertainty that we lived with created a surge in documented cases of depression and anxiety. During the pandemic, about 40% of adults in the U.S. reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder, up from about 10% in 2019[ii]. 40%!! That might not mean much out of context, so consider this: if 40% of the chocolate chips in your cookie didn’t taste sweet, you’d sure want to find out what you could do about it.

There are probably a lot of reasons why we’ve seen this jump during the pandemic and searching for a single silver bullet cause is wasted effort (complex adaptive systems, anyone?). But for futurists, there’s one facet that we can influence uniquely: hope. Sure, hope has gotten roughed up a little lately since it become a catchphrase in political campaigns, but there’s no denying that the prevalence of anxiety and depression are negatively correlated to people’s sense of hope[iii]. So, the less hope people have the more they feel anxious and depressed. But the more hope people have, the less they feel anxious and depressed. It’s that simple. Now, don’t get me wrong, foresight isn’t going to solve all the world’s problems. Every person must still be an active participant in managing their own mental health as far as they are able, but in addition to that, futurists can leverage their skills and platforms to make a constructive difference.

So, what can we do about it? Well, we can start with 2 not-so-simple ideas.

Trauma-informed futures

Technically, this isn’t a real thing yet. It’s an application of trauma-informed care (TIC) to our practice. Starting from the top, TIC is a set of practices used by medical professionals when interacting with patients that promotes a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing. It explicitly recognizes the role that a patient’s personal trauma(s) may have on the professional relationship and, by extension, the ability of the patient to receive care[iv]. In short, TIC can be exercised this way:

- Recognize how common trauma is and understand that every person may have experienced serious trauma. In foresight, this could be explaining why we ask certain questions or perform certain exercises during workshops. We can also patiently respond with compassion and work with people who are uncomfortable, rather than automatically excusing them from the activities. TIC could also affect how we present our work. Futurists like to talk about ever more immersive experiences, but the reality is, some experiences can be too realistic, in which case they’re reopening wounds, or even creating entirely new ones.

- Understand that there are many types of traumas. Life-threatening illnesses, abuse, failed goals, and pandemics are all trauma that can affect how people think about the future. As futurists, our best work is done by acknowledging that each type of trauma can uniquely impact their encounter with a visioning process, and even those wounds are valid elements of the future when properly understood.

How can TIC improve foresight? First, recognizing the role that trauma plays in people’s lives and how that affects their perception is an encouragement for participants to bring their whole selves to the process. That idea gets tossed about in contemporary corporate culture, but despite human resources departments’ best messaging, front-line employees are rarely empowered to actually share that much personality. For foresight, we NEED it. How can we claim to create organically-textured, true-color scenarios if we don’t have people sharing everything that they feel? That’s active diversity, equity, and inclusion. Second, when we pay attention to trauma, we cannot help but have that same compassion flow into the product of our work. And that change in our perspective is a subtle but powerful motivation to find ways to express the hope and optimism that hurting people need to carry on in the face of even the grimmest scenario.

Storytelling, Empathy, and Realism

I know what you’re thinking, “Yeah, storytelling is super important for connecting with people. Tell me something I don’t know, por favor.” That’s all true, but hang with me for a little bit, because that’s not my point. Instead, I’d like to suggest that our own attitude when we’re building and presenting our scenario-stories will affect how well we meet the needs of our audience. And that, will make or break the success of the project. Here’s a quasi-logical proof (thank you 9th grade geometry):

Storytelling is the key to empathy, and empathy is the key to user-centered design – when we serve others, our message grows.

You were ahead of me on the storytelling step, so I won’t spend time making the argument that storytelling is a powerful tool for connecting with people[v]. The next step, however, takes storytelling and adds a bit of interaction design method by intentionally focusing on the audience to understand their feelings and humanity not only to pick the right level of vocabulary but also to gain the insights that we want. We can then “empathize with them to understand their needs, thoughts, emotions, and motivations[vi].” So, adopting user-centered design techniques increases usability and thereby the likelihood of improved customer satisfaction and adoption[vii].

Now I can already hear some Cranky Nay-Sayer in the back of the internet nay-saying about how we’ll be watering down our work or preaching some absurd “future prosperity gospel” to a bunch of snowflakes. False. We certainly cannot back away from delivering the truth as we understand it and can support it. But that has little to do with the specific expression of the work that we present. A couple of ideas:

- Disclaimers/warnings/notices are an easy way to give fair notice that the content we are about to present might be difficult for some viewers. If Disney® can do this, so can we.

- Framing, context, and tone are Storytelling 101 methods for influencing reception. We can, of course, adjust the imagery, wording, motif, and concept organization, but until we critically assess ourselves, we might just jump from one misstep to another. Ask yourself these questions:

- Have I considered that my decisions can produce depression and anxiety in my clients?

- Have I considered that my decisions could encourage and help my clients heal?

- Am I framing concerns as obstacles/challenges or threats?

- Am I presenting my work from a place of frustration or collaboration?

- NB: This one is really subtle in its temptation. Thinking too much about critical, obstructive, or “backwards” points of view will come through in our work and will dim the value and meaning of our work.

- What does my work really say about me?

This last question is the most provocative and is informed by answering the question “Do negative people produce negative art or designs (also pronounced: scenarios), and vice-versa?” There’s not a lot of research that’s directly on point on this, but what there is suggests that there is a correlation between the creator’s outlook and the optimistic/pessimistic characteristic of the creation[viii]. So, if our scenarios are a subjective interpretation of our research and creative processes, and if we create primarily negative scenarios, are we really seeing a reflection of our own negative bias about the future?

Wrap Up

We’ve covered a lot of ground for a blog post, so let’s remember the key ideas:

- Trauma has always been a part of life, and usually more than we like to admit.

- The pandemic trauma has made anxiety and depression a much bigger problem that can affect the results of our forecasts and scenarios.

- Our work can affect the mental health of participants and consumers of our work because of the effect that it can have on hope.

- We can deliberately choose our techniques to emphasize restorative opportunity without sacrificing veracity.

- Physician, know thyself.

About the Author

Josh is a senior manager and foresight student. He’s as ‘at home’ in technology as the humanities, and it’s this adaptability that allows him to redesign, renovate, and restore ideas, processes, people, and products. He combines strong creative instincts with an analytical, systems-thinker approach to designing solutions that help organizations and clients’ see the beauty in new ways to produce optimal outcomes. He’s passionate about anything that can teach him how to think more clearly and broadly and you’ll never find him turning down an opportunity to explore. Every day, he tries to lead others by meeting their needs, and it’s this same attitude that draws him to foresight. Not only is it a blend of science, analysis, art, critical thinking, and commerce, but it also gives people a service that they need: a vision for the future.

[i] https://www.statista.com/chart/21878/impact-of-coronavirus-pandemic-on-mental-health/

[ii] “The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use”, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/adults-reporting-symptoms-of-anxiety-or-depressive-disorder-during-covid-19-pandemic/?activeTab=map¤tTimeframe=0&selectedDistributions=adults-reporting-symptoms-of-anxiety-disorder&sortModel=%7B”colId”:”Location”,”sort”:”asc”%7D; “COVID’s mental-health toll: how scientists are tracking a surge in depression”, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00175-z

[iii] “Interaction of hope and optimism with anxiety and depression in a specific group of cancer survivors: a preliminary study”, https://bmcresnotes.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/1756-0500-4-519.pdf; “The Relationship between Basic Hope and Depression: Forgiveness as a Mediator”, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11126-020-09759-w

“[iv] Trauma-informed care: What it is, and why it’s important”, https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/trauma-informed-care-what-it-is-and-why-its-important-2018101613562

[v] “Empathy in the Time of Technology: How Storytelling is the Key to Empathy”, https://jetpress.org/v19/manney.htm

[vi] “Stage 1 in the Design Thinking Process: Empathise with Your Users”, https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/stage-1-in-the-design-thinking-process-empathise-with-your-users; “Design Thinking: Getting Started with Empathy”, https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/design-thinking-getting-started-with-empathy

[vii] “User Centered Design”, https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/user-centered-design

[viii] “Creative Self-Efficacy and Innovative Behavior in a Service Setting: Optimism as a Moderator.”, MICHAEL, L. A. H., HOU, S.-T., & FAN, H.-L. (2011). The Journal of Creative Behavior, 45(4), 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2011.tb01430.x

[ix] https://imgflip.com/memegenerator/104851223/Spiderman-mirror

[ix]

[ix]