This is a continuation, Part 2, of my COVID19 posts – you can look back to Post 1 for the framing of the topic. This post continues to dig in with a little more background and some current assessment and then for Part 3 we can get down to some alternative futures.

We have lived with several pandemics in history.

Our handling of these has varied – ranging from prayer and scented herbs to fight the miasma to Hazmat suits, antiseptic foggers, and jab roulette for the A, B, C, D, E’s of the flu. As science has come to the forefront we have more tools, more information (and mis-information) to help, but from the Early middle ages to now there are some similarities to our pandemic care and prevention.

For the Justinian Plague – as a reaction to the deaths, taxes were raised, new laws were written to deal with the large number of people dying without wills, new border aggression arose and political alliances changed as some states were weakened and some stayed strong. It is thought that this plague may have directly strained the Byzantine Empire’s military and economy to the point that its decline was inevitable.

Some medical treatments for those ill with this plague from an (on line) Ancient History Encyclopedia article included doctors at the time which might lance your swollen lymph nodes to release humors, or home remedies, “ including cold-water baths, powders “blessed” by saints, magic amulets & rings, and various drugs, especially alkaloids. Some were simply locked away in quarantine to die or not, the survivors of which were credited with “good fortune, strong underlying health and [a strong] immune system” (Rosen).

800 years later, the handling of the Black Death was not much better. Muslim religious scholars taught that the disease was a “martyrdom and mercy” from God – and a punishment for non-believers. Christians increased prayer, but some say that faith in religion decreased after the plague because of the failure of prayer to stop the deaths and the ravage of the clergy by the disease. Economically, the deaths of so many made labor scarce and higher wages were demanded by the peasants (think essential workers). The prices for all of the scarce goods inflated. Fashion changed as the nobility sought to differentiate themselves from the newly prosperous peasantry. And since this socio-economic disruption occurred just before the Renaissance it is thought to be responsible for emergence of unequaled art, literature, and architecture.

From the (on line) Ancient History Encyclopedia – Animal cures, Potions, Fumigations, Bloodletting, Pastes, Flight from Infected Areas, Religious Cures, and Quarantine and Social Distancing were tried. “Of these five, only the last – quarantine and what is now known as “social distancing” – had any effect on stopping the spread of the [Black Death]. Unfortunately, people in 14th-century CE Europe were as reluctant to stay isolated in their homes as people are in the present day during the COVID19 pandemic. The wealthy bought their way out of quarantine and fled to country estates, spreading the disease further, while others helped with the spread by ignoring quarantine efforts and continuing to participate in religious services and by going about their daily business.” https://www.ancient.eu/

Before we enter the Modern Era we will take a quick look at my so-called Transition Era (nominally 1400 to the late 1800’s).

I’m showing just two pandemics during this period – both horrible but both very localized; the 1629 Italian Plague and the 1665 London Plague. At this time the global population was in the half billion range. The Italian Plague claimed a million lives in northern and central regions of Italy. At this time there were more treatment and separation measures such as putting the plague hospitals outside of the city walls and a secret balm named Composito was available to be applied to the body in a ritual that included burning scented woods. There was in inkling that there existed “seeds of disease” in a theory published by Girolamo Fracastoro and cities were cleared of garbage and stray animals in an effort to sanitize.

The other horrible pandemic, the 1665 London Plague, claimed a 100,000 souls there (thought to be around a quarter of the population of London). It was one of the last hoorahs of the bubonic plague and led the British in May of 1664 to quarantine ships and persons from 29 countries as the plague was erupting across the continent. But it was too late.

Which brings us to the Modern era.

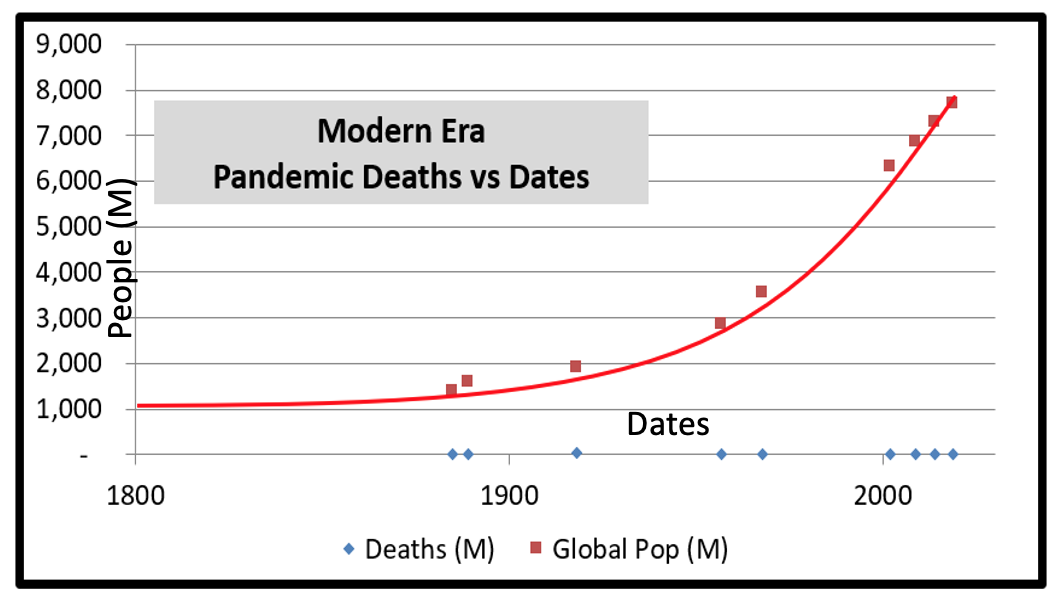

Here is another look at my graph:

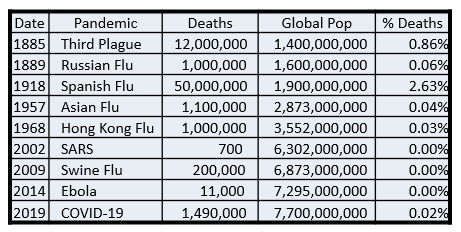

My chosen data is for these 10 pandemics that met my truncation criteria:

Table 1

My Modern Era starts off with the Third Plague of 1885 which was another pandemic that took it’s toll primarily on one location but “leaked out” to others – originating in Southern China and carried by steamship from Hong Kong to all major continents. Based on a research paper by Ole Sonne, “The French bacteriologist Alexandre Emile Jean Yersin isolated in 1894 and identified Yersinia pestis as the contagious agent in Hong Kong despite obstructions from the British authorities who favored Shibasaburo Kitasato from Japan. Four years later the French scientist Paul-Louis Simond established the rat flea, Xenopsylla cheopis, as the vector transferring the bacteria from rats to humans. This discovery was, however, not recognized until 1903 and another five years passed until clinical consequences were taken during the plague epidemic in India 1908.” The answer was there, but not recognized until after the loss of 12 million souls.

This really was a last great hoorah of the Black Death – pandemics thereafter began to affect as pneumonic as opposed to bubonic (respiratory focused as opposed to lymph focused). Influenza became the killer of the masses – air and surface borne – moving from person to person in the crowded urban environs [urban concentration hits 30% in the 1950’s and keeps swelling] overloading hospitals, mortuaries, and funeral homes.

For the bubonic plagues we found that standards of sanitation, animal control, and as the last resort, antibiotics for those unfortunates that are infected work to prevent pandemic recurrence. In the absence of the knowledge of infection vectors and the modern tools and medicines, we find that what still works is isolation, quarantine, and distancing. If I am not around someone or something that is carrying the disease, if we stay far enough apart, and we treat things that we might share to remove the bugs – I don’t get sick. This is the oldest, most common, and most successful formula – avoid infection. It is distinctly different from the pox parties of my youth where moms in the neighborhood would expose children to each other to make sure they got sick with mumps, measles, and chicken pox at a young age so that they wouldn’t have to worry about having the diseases later. This still goes on with the anti-vax crowd and you have probably seen some news about herd immunity, and COVID parties which is related somewhat.

Herd immunity is a thing – some of us are bound to be genetically disposed to do better with disease than others. It’s a callous, pragmatic view which has some trouble fitting into our values shift as we become more integral. But there it is – none of us will make it out of here alive.

The Spanish flu was a vivid reminder of our fragility in the face of novel diseases. Around 3% of the global population died. Worst hit was India which may have lost as many as 20 million souls to the disease. In the US according to an excellent post at www.virus.stanford.edu at a military training camp during the influenza epidemic swabs and specimens were collected and studied for the causal organism. Commonly found were pneumococcus, streptococcus, staphylococcus and Bacillus influenzae (JAMA, 4/12/1919). This testing used “in the clinical setting brought in a solid scientific, biological link to the practice of medicine. Medicine had become fully scientific and technologic in its understanding and characterization of the influenza epidemic.”

We were applying our technology to the problem as well as the sanitation and separation tools, but the first flu vaccines were not to come until the 1930’s with widespread availability delayed until 1945.

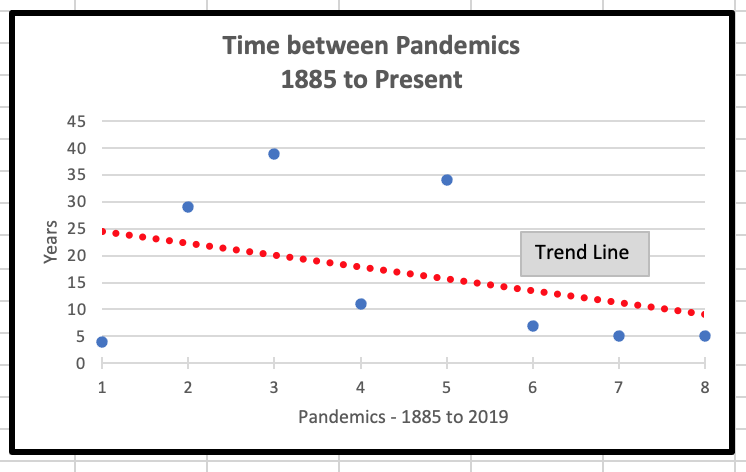

Which brings us to the modern era. Disturbingly, pandemics seem to be happening more often. The graph below of the data in Table 1 hints at this:

While we have a great bumper of population to take these savage assaults, a world with only 5 to 10 years between pandemics will be different.

In a recent fireside chat with another futurist we were brainstorming up the end of era disruptive forces that seem to be dominating our futuring these days. Among them were:

- End of capitalism

- economics

- future of work

- wealth divide

- Values shift

- Climate change

- Energy Shift

- Political System’s shift (US)

- Gender definition shift

- Civil Policing definition shift

- COVID19

The list goes on, but this is enough for now.

Given the variety of pandemic experiences any given group is probably influenced by several or a few of these forces. For example:

- Those in the medical profession wearing more gear and working heavy hours with surrounding comrades in varying stages of illness, quarantine, and PTSD are also seeing people’s pronouns change. The police that they work with on the emergency care lines are under huge stress and behaving differently. Like the pandemic? Let’s have a world record season of destructive weather on top of that! And their future of work is now sitting with patients in Zoom sessions complete with barking dogs, crying children, and buzzing mobiles as they try to deliver care for the patient without becoming one themselves.

- An engineer has been home since March when the cases in the office building got too high to ignore. There was work for a few months then the company had to get creative with Company Convenience Leave, some payroll assistance from the government, and finally severance and redundancy. Being home left more time to watch the spiraling US presidential election vitriol, the inner-city riots for mattering, and the weather news.

- A warehouse worker or delivery driver at the bottom third of the median income is suddenly an “essential worker”, pressed into longer hours with little protection from illness at interfaces with fellow workers and the general public and is wondering why essential does not mean well paid.

- A new elementary school teacher begins work as the pandemic first sends students home and then back into the classroom in a school district little prepared for any such technology and curricular emergency. The teacher struggles to overcome work obstacles while trying to balance life with three young children (two of school age), a work from home sales executive spouse, and procuring basic household supplies, good nutritional food, regular home maintenance and unexpected repairs caused by the continuous demands of the stay-in family.

- A retired couple with co-morbities hunkers down – isolating from children and friends, stocking up like their grandparents from the Depression era, wondering where the civility went in all of the media streams and when things will get back to “normal”.

- A worried spouse comforts a child as the chief wage earner of their small household is wheeled out on oxygen and a drip bag to a waiting ambulance by gowned and masked EMTs on the way to a hospital that cannot be visited.

- A family bitterly watches a virtual funeral for the family matriarch. The chat section is closed down at the request of the survivor because of racist sniping at the last family “gathering”.

- Oil tumbles and bounces as major corporations declare themselves to be in the “carbon management” business as all the while solar steadily wedges in.

Many different walks of life, all under the influence of the great shutdown, the new quarantine, of 2020 and the changes of our times.

Looking at the AHA.ORG website that keeps a page – Fast Facts on US Hospitals, we see they list 5198 Community hospitals in the US. Community hospitals are defined as all non-federal, short-term general, and other special hospitals which includes obstetrics and gynecology; eye, ear, nose, and throat; long term acute-care; rehabilitation; orthopedic; and other individually described specialty services as well as academic medical centers. Excluded are hospitals not accessible by the general public, such as prison hospitals or college infirmaries.

Combined, these Community Hospitals offer about 800,000 staffed beds – of these, approximately 78,000 Intensive Care Unit (ICU) beds are useful for seriously ill pneumonic plague victims. In the US (as of 12/21/20, Google) 17.9 Million persons have been determined ill, and 318,000 have died. The Stanford school of Medicine says that 60% of Americans die in hospital, 20% in nursing homes, and 20% at home. Using this as a broad generalization that would mean that over the past nine months, if 1 in 6 ill will require hospitalization, that means that approximately 3 million have spent time in hospital sharing those 800,000 beds while (using the Stanford premise) about 200,000 have died in hospital most likely sharing the 78,000 ICU beds with the rest passing in nursing homes and at home.

Of course – the illness moves in spikes and easily overwhelms the regional resources – it does not affect evenly across geography. You can imagine the horrors on American streets if the Black Death was stalking the nation killing 57% of the population or about 180 million dead.

These are the “problems” of our current situation that I see. In my next blog post (or two) I will take a swing at what these situations mean for the futures.

Continue reading in part three…